Introduction to Gross Anatomy and Physiology of the Equine Hoof

The reader should bear in mind that this text is not intended to be a fully detailed text on the anatomy or histology. The intention of this chapter is to highlight those aspects of the limb’s structure and their relationships most integral to the hoof and its role in locomotion. Further detail on the anatomy and histology of hoof horn and the other structures of the digit can be found in the scientific papers cited within this chapter.

The necessity for the study of anatomy

A farrier needs to have a good working knowledge of the anatomy (structure) and the physiology (function) of the horse and a detailed knowledge of the limbs of the equine particularly the lower limbs including the carpus (knee) and tarsus (hock). Because he/she is dealing with a living structure and his/her work can and does affect the performance and wellbeing of the whole animal he/she should also have a thorough working knowledge of the overall musculoskeletal unit.

The structure and function of the foot

The foot and hoof have three main functions, shock absorption, stabalisation and support for the musculoskeletal structure at rest or during motion and finally to facilitate movement. A high percentage of lower limb lameness problems either occur within or originate from the foot. Many of these lamenesses are often associated with continuous or repetitive strain caused bio biomechanical dysfunction. It is incumbent on every farrier should be aware of the anatomy, physiology and biomechanical functions of all structures within the foot enabling him or her to achieve the optimum biomechanical efficiency of the foot and limb and to have the confidence when dealing with both normal and abnormal foot conformations and associated lamenesses and pathologies.

A fundamental principle of farriery is to achieve equilibrium of static and dynamic forces acting on internal structures within the foot and lower limb. External influences should be neutralised by internal forces with the form of the foot maintained so as not to inhibit its natural function. Farriery attempts to maintain equilibrium within the foot by trimming to achieve an ill-defined and subjective empirical interpretation of “Static Foot Balance” (Hickman & Humphrey 1987; Stashak 2002). This interpretation of foot balance is mostly derived from historical texts (Dollar & Wheatley 1898; Russell 1897; & Lungwitz 1891). Today’s modern domesticated horse is far from the forces of nature that historically shaped and controlled their development. Horses are more reliant than ever on the knowledge and skill of the hoof care professional with an understanding of the anatomy, physiology and function of the lower limb, foot and all its component parts. The composition, position and functional relationship of the component parts of the foot are so densely compacted that within the hoof capsule there is little room for manoeuvre.

In nature shape and form of a structure relate directly to function. The hoof capsule is such an example of this concept. A horse’s natural protection against predators is “fright and flight” the hind quarters of the horse are a compact mass of large loco motor muscles which are designed primarily to propel the horse quickly forward. The front limbs are designed to primarily support the horse through impact, deceleration and loading during locomotion (Back & Clayton 2001). Movement is effected via neurological impulses causing the limbs to retract or protract. To minimise the energy required for this movement the limbs are as light weight as practical and are manoeuvred via a series of levers and pulleys. The pulleys are the joints, which are held together with a complex array of ligaments. The levers are the tendons which, together with the ligaments, act like a coil spring releasing stored energy when movement is necessitated. In simple terms every time the limb is loaded the elasticated collagen fibres that make up the tendons and ligaments store energy which is released when the limb needs to be lifted and propelled forward.

Anatomical Considerations

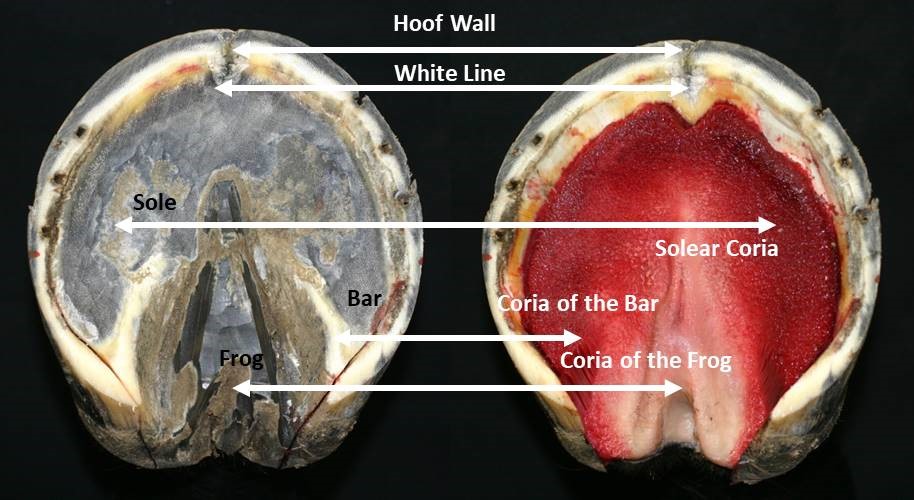

The gross anatomy of the foot and limb is well documented. In farriery the foot of the horse is referred to as the keratinized hoof capsule and its contents (figures 16 & 17). The hoof capsule is a continuation of modified epidermal tissue which forms a firm yet flexible protective layer surrounding the skeletal components at the distal extremity of the limb (Kempson. 1987, Dyson, 2011). The primary functions of the hoof capsule and its associated structures are to absorb impact shock during locomotion, assist in the transfer of weight from the skeletal column and protect the underlying structures whilst providing grip during locomotion (Butler 2005).

Each epidermal structure has a different density and hardness dependent upon its primary function and is produced by its own corresponding dermal layer and gains its strength and flexibility from its chemical composition and moisture content. The outer layer of hoof wall is rich in disulphides giving additional strength. The sole and frog are rich in sulfhydryl a group which gives these structures greater elasticity (Pollitt 1988) which gives flexibility. The average growth rate of 6-8mm per month (Stashak 2002) is said to be equal to the wear of the foot at the bearing border ground interface (Back and Clayton. 2001).

The hoof is the ultimate focus of forces generated by the limbs’ dual functions of weight bearing and locomotion. It is the only part of the horse’s anatomy whose shape, and consequently functions, can be altered readily. Hoof shape can be changed by the way those forces are directed into it (the way a horse moves), by weakening effects of environment, and by trimming and shoeing practices. Conversely, altering hoof shape can alter its functions and thus effect the movement and health of the limb above it. Because of this complex dynamic relationship between hoof shape, locomotion, environment and hoof care, detailed knowledge of hoof structure and function is essential for the practices of farriery and lameness related equine medicine.

The horse hoof is a horny covering on the end of each limb’s digit. Its purpose is in providing the limb with traction and protection. All such horny appendages are formed of keratinized protein. Among quadruped mammals, most have from two to five digits on the end of each limb that comprises their toes. Those mammals with two toes (deer, cattle, etc.) are termed “cloven hoofed.” The third phalanx of each of those two digits is encased in a hard, horny shell shaped something like a crescent to half circle. Together these two “claws” form a roundish base of support for the limb. The horse, however, has only a single digit on the end of each limb and thus its hoof is a single, solid horny case covering its single third phalanx. This single hoof distinctly resembles the two halves of the cloven hooves of larger two-towed quadrupeds “fused” together. Though these single and double digits are markedly different, they both must fulfil similar functions ultimately; supporting body weight and providing for locomotion while dissipating the shock and compression of these efforts.

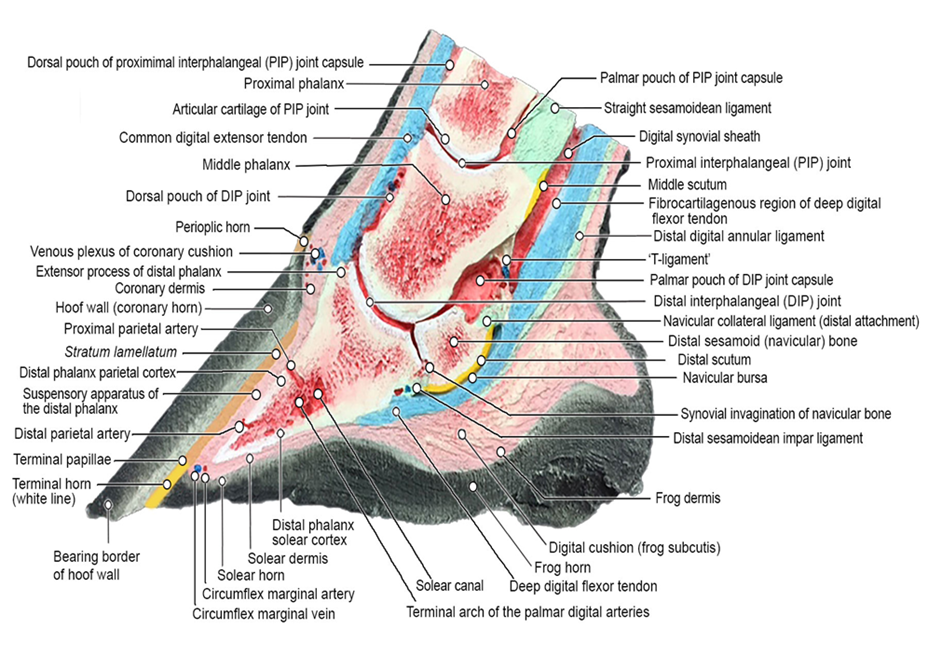

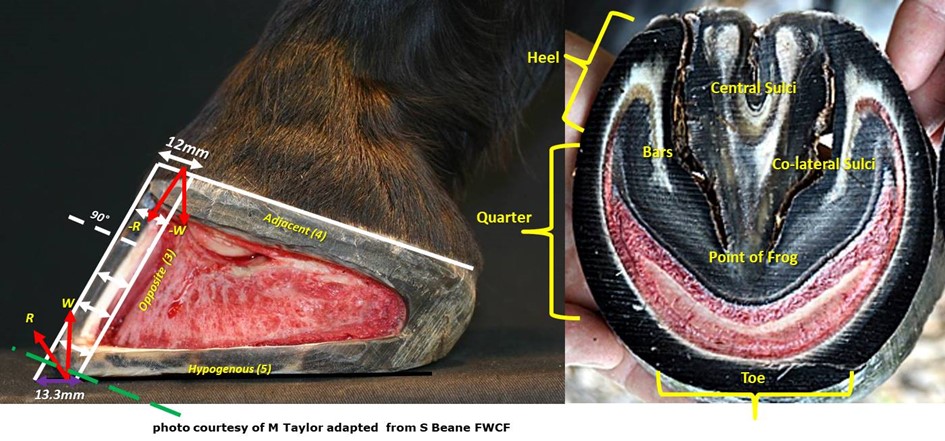

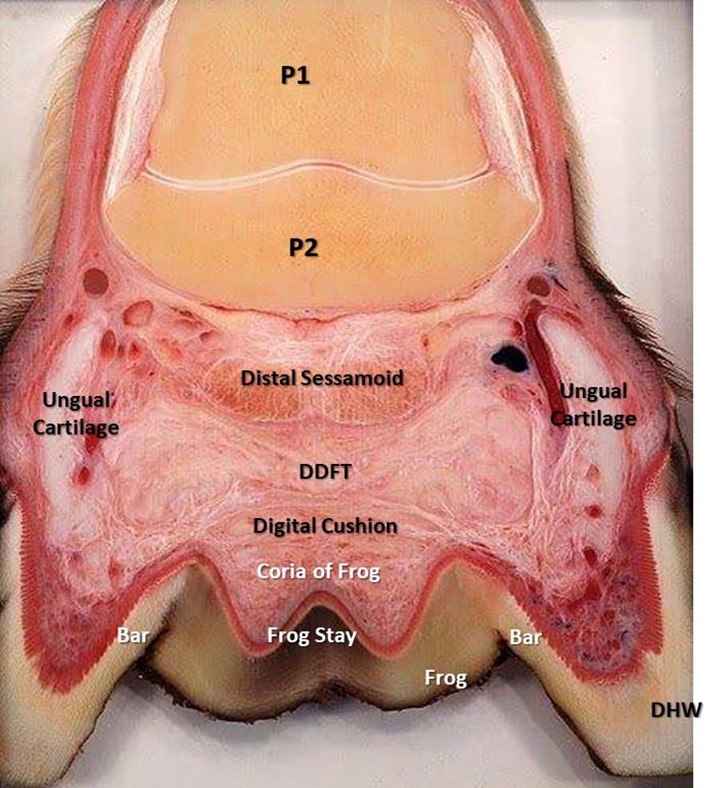

The hoof capsule encapsulates the structures of the foot including the distal interphalangeal joint (DIP joint), distal phalanx (P3), distal sesamoid (navicular) bone, dermal laminae, collateral ligaments, cartilages of P3, digital cushion, termination of the deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT) and a network of arteries, veins and nerves (Figure 2). The external bearing surface is comprised of the horny sole, white line and frog (Stashak, 2002). The hoof wall consists of three layers; the stratum external, stratum medium and the stratum internum (Stump, 1967, Reilly et al., 1996) The inner layers of the hoof wall, the stratum internum, consists of around 600 non-pigmented keratinised, primary epidermal laminae, each of which bears 100-150 non-keratinised, secondary epidermal laminae (SEL) (Stump, 1967). Pollitt (2001) confirmed that the SEL dovetail with their adjacent counterparts of the secondary dermal laminae (SDL) of the laminal corium (Figure 3), which covers the parietal surface of P3, suspending P3 within the hoof capsule. Between the dermal epidermal laminae there is a thin epithelial cellular layer, described as the basement membrane (BM), which undergoes constant remodelling (Pollitt, 2001). As a result the SEL slide past the SDL by breaking and reforming in a staggered ratchet-like manner so that the keratinised cells can move distally yet still support load (Pollitt, 2004).

The Component Parts of the Hoof

The insensitive horny hoof or hoof capsule consists of four basic component parts. These are the “wall,” the “bars,” the “sole” which covers most of the hoof’s lower or volar surface, and the wedge-shaped “frog” found on the volar surface between the bars and sole (figure 18). These parts, while produced by differing areas of sensitive tissues and composed if differing cell structures, are all fused together to form a single, flexible casing that is open at the top. Growth rates and amounts of horn in each hoof part can vary considerably relative to each other and between individuals.

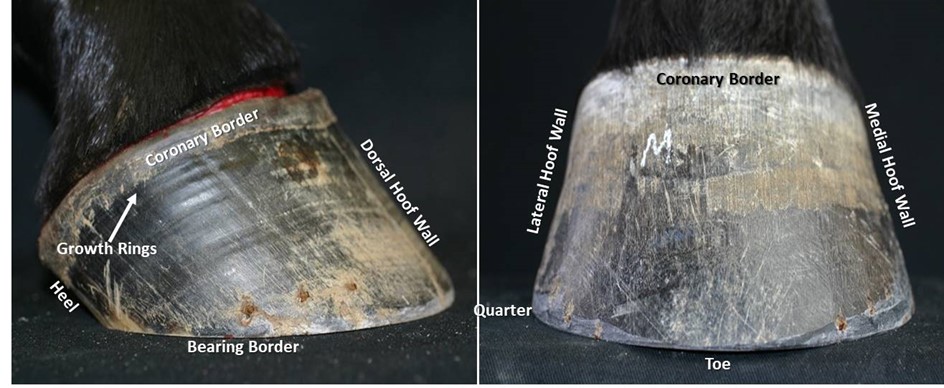

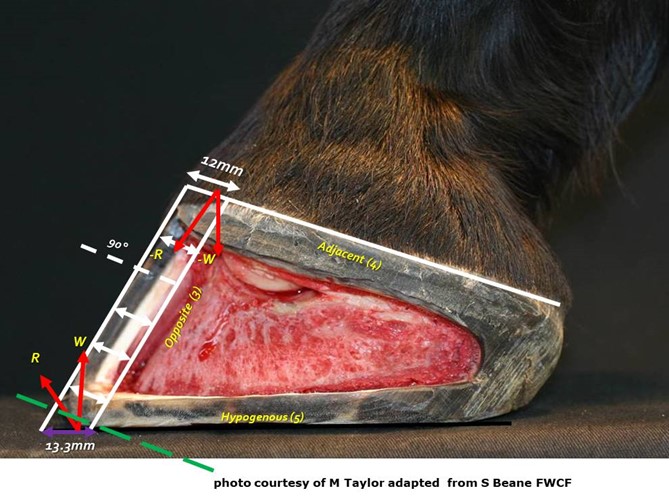

The hoof wall is the vertical structure arranged around the outer surface of the third phalanx, sloping forward and, to some degree, outward from the hairline region knows as the coronary band or border of the hoof. The wall is constructed of vertical tubules which are said to be parallel to the anterior surface of the third phalanx, the angle at which weight is loaded onto the wall from the bone. The name coronary band is derived from the high percentage of blood vessels contained in it. The wall’s dorsal aspect is termed the hoof’s toe. The middle halves of its medial and lateral sides are called the hoof’s quarters or side walls. The posterior sections of the wall, beginning behind its widest point on each side, are termed its heels. That widest aspect of the side walls is known as the “bend of the quarters”. The heel region includes the end of the wall where it meets the bars. This angles juncture of wall and bar is called the buttress of the heel (figure 4). The wall itself is thickest, horizontally, at the centre of the toe where it is approximatly10mm to 12mm across. From that point it tapers to its thinnest points near the bend of the quarters. It then normally thickens as it becomes the heel and heel buttress. The wall serves primarily to support body weight transmitted through its connection to the third phalanx as well as provide traction where its bearing border interacts with the ground surface.

The bars are actually continuations of the wall itself, turned inward and forward from the buttresses of the heel. The space between the wall of heel and the bar just forward of the buttress is termed the angle of the wall. The bars have some vertical height, like the wall, which diminishes to nothing toward the point of the frog (figure 4). The bars are slanted at an angle to the ground similar to that of the wall, so that their upper borders inside the hoof are closer together than their lower one on its volar surface. But the vertical surfaces of walls and bars are not parallel. The bars serve to reinforce the outer wall of the hoof by bracing and anchoring the heels, and also act to support the frog between them.

The frog is a mass of rubbery horn situated between the buttresses and bars, tapering forward toward the toe. Deep grooves on either side of the frog, separating it from the bars, are referred to as the collateral sulci or the commissures. Its narrow apex end is known as the point of the frog (figure 4). The groove or depression on the frog’s palmardistal surface which divides it into two halves is its central sulcus, sometimes termed the cleft. On the upper or interior surface, inside the hoof, the central sulcus forms a protrusion known as the frog stay (figure 5). The frog is supported on either side by the bars to which it is fused and serves primarily as a protective pad for the sensitive parts contained in the hoof above it.

Above and palmar aspect of the frog is a region called the bulbs of the heels. These two bulges below the hairline, from which the buttresses of the heels originate, are a thin covering of horny material over the soft palmaproximal border of the digital cushion. The horn of the bulbs helps protect the palmar structures of hoof including digital cushion.

The horny sole is the region of the hoof’s volar surface bounded by the bearing surface of the hoof wall, the bars and the frog. It tends to be concave rather than flat, arching up into the curvature of the third phalanx’s distal surface (figure 20). The sole is attached to the inner border of the wall by a flexible strip of horn called the white line (figure 4 ) binding the sides of the wall together laterally across the hoof, as well as to the frog and bars at their common borders. The vertical thickness of the sole is normally between 10mm and 12mm. It serves to It also protects the sensitive tissue above it from injury.

The Hoof Parts as a Whole

The hoof as a whole serves two basic functions. 1) Its overall shape is a medium for support and traction in locomotion. 2) It provides protection to the sensitive parts within and above it by being a resilient covering and dissipating internal pressures through its elastic composition and expansive actions. These functions require conflicting properties of rigidity for support/traction and flexibility for shock dissipation. Both the design of the hoof’s overall shape and the material properties of the horn from which its parts are formed enable it to perform these dual functions effectively.

The hoof wall is extremely efficient at defusing shock vibrations generated when the hoof impacts the ground during locomotion. It is able to reduce both the frequency and maximal amplitude of the vibrations (Dyhre-Poulsen et al., 1984). By the time the shock of impact with the ground reaches the first phalanx up to 90% of the energy has been dissipated, mainly at the lamellar interface.

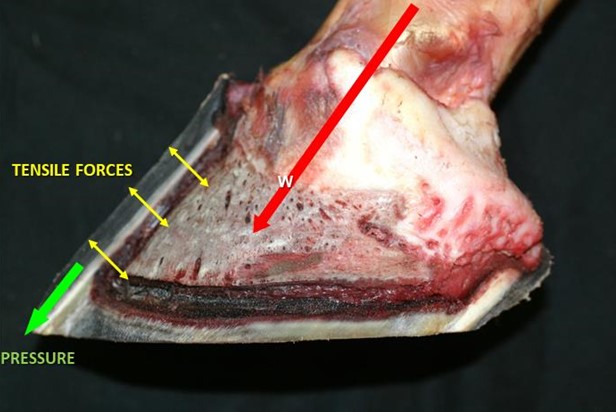

The overall shape of the hoof is dictated by the direction from which weight and force are exerted upon it. Since weight is transmitted downward and forward through the bones of the digit, the hoof grows so that its greatest strength is aligned with those bones (figure 2). The impact of weight is thus thrown upon the more rigid forward aspect of the hoof wall, while its descending forces and those of propulsive effort are dissipated by the more elastic structures situated in the “gap” between the ends of the hoof wall at the heels.

The bars direct any weight falling on their upper border out toward the heels and wall, while at the same time limiting the expansion of the heels to avoid their collapse. The frog accommodates the lateral spreading of bars, heels and quarters under pressure by stretching laterally itself. A vertical section through the palmar third of the hoof shows this lateral spring structure of wall, bars and frog (figure 5). For the expansion and thus protective actions to occur, there must be some vertical length bars and the wall in the heels. It is important to understand that individual hoof walls come in various degrees of flexibility and will deform in any direction when a sufficient force from any angle overcomes the limits of the horns elasticity, consequently we must understand the usual forces applied to a hoof capsule and its morphology during locomotion to get any idea of what is normal distortion. Also we must consider the effects of not only the ground’s reaction but the changes in weight bearing caused by the animal’s centre of weight gravity as it moves over the hoof. The effects of weight bearing during the stance phase will be discussed in detail in a subsequent post.

Epidermal structures within the hoof

The Hoof Wall

It is generally accepted that the hoof wall does not vary in thickness from its origin at the coronary band to its conclusion at the distal border. The wall is thicker at the toe and becomes progressively thinner and more elastic toward the heels where it thickens again where it reflects dorsally as the bars. This variation in hoof wall thickness is believed to be of importance in facilitating hoof function (Douglas et al. 1996, Pollitt 1996, O’Grady 2009 and Hampson and Pollitt 2011). When viewed from the solar surface the thickness of the hoof wall, around the foot’s circumference, can be evaluated to determine how much hoof might be removed when trimming or shoeing. This view can be misleading as to the true thickness of the hoof wall because the wall has either been pared or worn parallel to the ground surface. This creates a misleading view and could lead to an inaccurate assessment and is largely due to the angulation of wear or trim occurring across the dorsal hoof wall instead of at a right angle (figure 7). Balchin (2012), in a study of the sagittal section of 200 cadaver front feet, demonstrated that the coronary band and DHW where at right angles and formed a right angled triangle with the DHW and bearing border. The DHW is said to be of uniform thickness when viewed in a transverse section from its origin at the coronary border to the ground bearing border and parallel to the dorsal surface of P3. However the BB of the DHW presents perpendicular to the axial skeleton and oblique to the coronary border and is therefore increased in width at the perpendicular ground-bearing surface (figure 21A). Numerous authors have identified the importance of a hoof wall gradient from toe to heel, from both an anatomical and engineering prospective. Moore (2017) concluded that the natural circumferential toe to heel gradient of 1.77:1 was less than previously thought. Beane (2018) supported this contention and gave consideration to differential trimming protocols of the DHW and demonstrated a significant difference in solar arch morphology where the DHW was reduced through dorsal wall rasping.

The hoof wall is made up of three layers: the stratum extremum, the stratum medium and the stratum internum. The stratum externum, or external layer of the hoof, consists of an extremely thin layer of tubular horn. It includes the periople, which covers the bulbs of the heels and a variable tubular horn. The remainder of the wall is covered by the stratum tectorium (also part of the stratum externum) which has a high fat content and so helps to prevent the movement of water through the hoof wall. It is this layer which given the un-rasped wall its shiny appearance.

The stratum medium, which comprises the bulk of the hoof wall, is composed of tubular and intertubular horn. It is this part of the wall which is produced by the coronary corium. In dark hooves, this layer is pigmented with melanin. Although there is a widespread belief amongst that white hooves are inferior to dark hooves, differences in the mechanical properties of pigmented and non-pigmented hooves have not been demonstrated. The stratum internum is the name given to the internal layer of the hoof wall and comprises the primary and secondary epidermal and dermal laminae. This region is always non-pigmented, even in dark hooves.

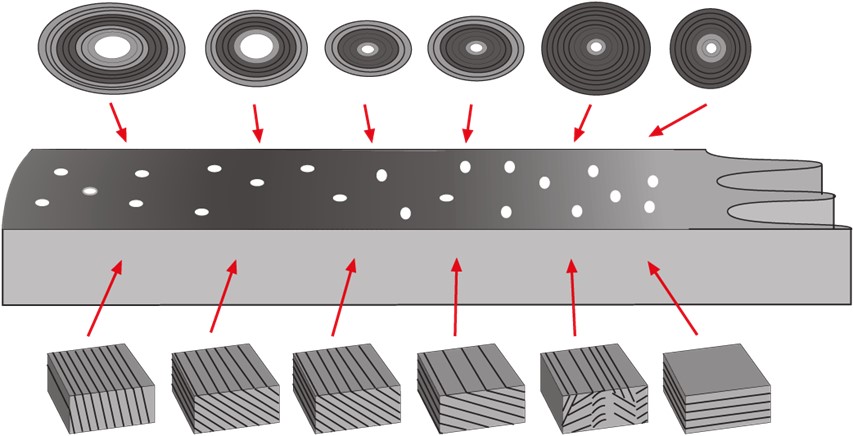

The horn itself is composed of densely packed, longitudinally aligned, horn tubules which are generated from tiny projections of the dermis known as papillae (figure 8). These tubules are cemented together by intertubular horn cells which proliferate from germinative cells of the dermis between the papillae.

The intertubular horn is formed at right angles to the tubular horn and gives the hoof wall a mechanically stable, multidirectional, fibre-reinforced composite (Bertram and Gosline, 1987). Interestingly hoof wall is stiffer and stronger at right angles to the direction of the tubules. This contradicts the usual assumption that the ground reaction force is transmitted proximally up the hoof wall parallel to the tubules. The hoof wall appears to be reinforced by the tubules but it is the intertubular material that accounts for most of its mechanical strength stiffness and fracture toughness. The tubules are three times more likely to fracture than intertubular horn (Leach, 1980; Bertram and Gosline 1986).

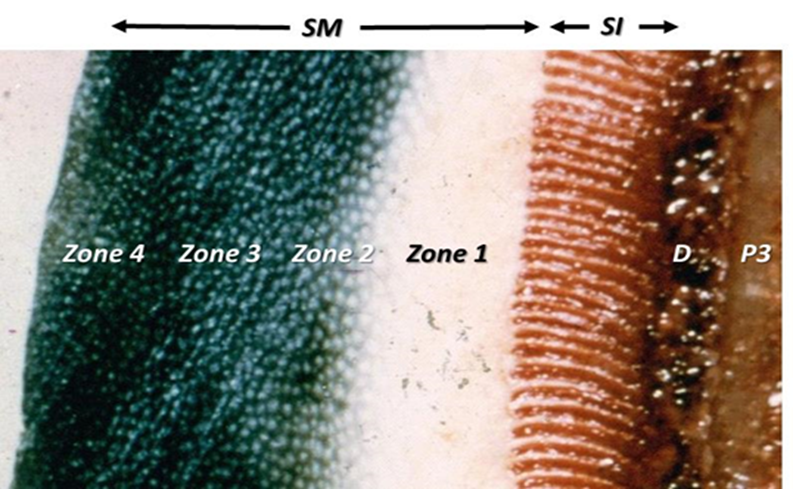

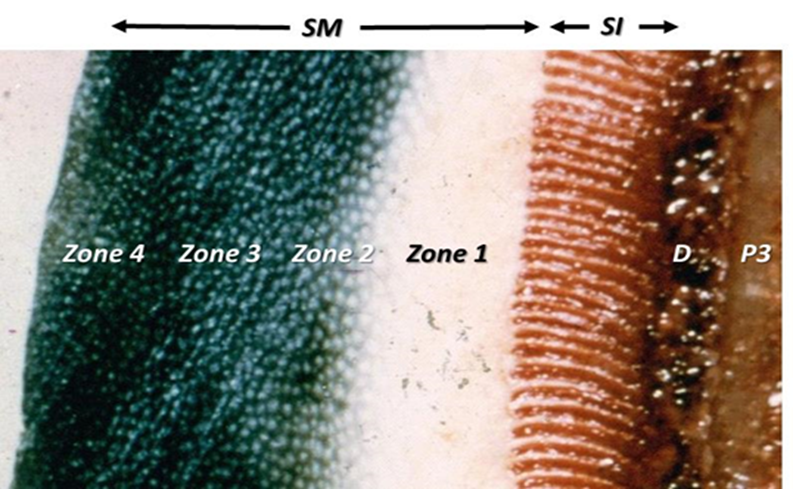

The bulk of the hoof wall consists of the stratum medium, which is the main load bearing part of the hoof wall, and extends from the coronary band (CB) to the bearing border (BB). Its generation is from the epidermal basal cells of the coronary corium (Stump, 1967; Pollitt, 2001) and it is a non-homogenous and anisotropic material within which horn tubes run diagonally from the CB to the BB. The horn tubules are arranged into four zones of density (Reilly et al. 1996), the strongest and most densely populated zone being the outer layer. Intertubular horn is formed at right angles to the tubular horn, filling the void between the horn tubules (Bertram & Gosline, 1987). Interestingly, hoof wall is stiffer and stronger at right angles to the direction of the tubules, a finding at odds with the usual assumption that the ground reaction force is transmitted proximally up the hoof wall parallel to the tubules. The hoof wall appears to be reinforced by the tubules but it is the intertubular material that accounts for most of its mechanical strength stiffness and fracture toughness. This construction achieves mechanical stability within the horn with the mechanical properties of the horn tubules being best suited to compressive force with the intertubular horn providing stability through tension (Bertram & Gosline, 1987). The equalisation of both compressive and tensile forces allows ground reaction forces to be dispersed within the structure without regional overload (Thomason, 2007). However a recent study (Lancaster et al., 2011) found a circumferential zonal pattern of tubule density with the medial and lateral locations showing the same radial pattern, but there was a significant difference in tubule density between the medial and lateral sides, and between the toe and the lateral quarter.

The highest tubular density is at the outermost layer (figure 9). Since the ground reaction force is transmitted proximally up the wall (Thomason et al 1992) the construction of the epidermal structures appears to be part of the mechanism that allows the transfer of impact load across the hoof wall from the rigid, high tubule density, outer wall to the more plastic, low tubule density, inner wall. The material properties of hoof are said to have plastic elastic characteristics (Reilly et al; 1996). These characteristics allow for deformation under stress and then return to original form following a limited period of strain. Maximum stress for prolonged periods of strain reduces the elastomeric property and the structures ability to return to its original form.

In a normal foot the entire hoof wall grows at a rate of approximately 6 to 10 mm per month. Growth is slower in excessively cold or dry environments. At the toe, it takes approximately 9 to 12 months for horn to grow from the coronary band to the ground surface, at the quarters 6 to 8 months, and at the heels 4 to 5 months. Because the distance from the coronary band to the ground is less at the heels than at the toe, heel horn at the ground surface is younger than toe horn, has higher moisture content and is more elastic. Significant changes in nutritional status, or persistent fever states, may cause changes in the growth of the hoof wall at the time of the “insult”. These become apparent as rings or ridges in the hoof wall, which then grow out with the hoof. The rings are usually roughly parallel to each other and to the coronary band. These should be contrasted with the rings on the hoof of a horse which has previously been affected by laminitis. “Laminitic” rings usually do not grown out parallel to each other because after laminitis as growth is often restricted at the toe resulting from disruption of the vasculature. Thus the ring is formed at the coronary band at roughly the same time all around the hoof, but the continued or accelerated heel growth causes sequential rings to diverge from each other at the heel as the hoof grows out.

Similar to any other epidermal structure, it prevents absorption of water into the body from the environment and prevents loss of fluids from the body. It is effectively a “waterproofing layer”. But the function for which it is uniquely designed is that of weight bearing. The weight of the horse is transmitted down through the column of bones in the limb, ultimately being borne by the coffin bone.

Tightly adherent to the external surface of the coffin bone are the dermal laminae of the laminar corium. The tight interlocking of the dermal laminae with the epidermal laminae on the inside of the hoof wall allows the weight of the body to be transmitted via tensile force from the P3 to the hoof wall. Effectively the bodyweight is said to be “suspended” from the inside of the hoof, the ground reaction force being taken by the hoof wall.

There are some 600-900 primary laminae (figure 10) each with 100-200 secondary epidermal laminae (Pollitt. 1988). The primary epidermal laminae are produced by the dermis of the coronary corium. The secondary epidermal laminae are produced by a germinative layer of the epidermis of the laminar corium. The primary and secondary epidermal laminae interdigitate, dovetail, with the corresponding dermal lamellae. The dermal lamellae originate from the laminar corium surrounding the parietal surface of P3 and the lower border of the ungual cartilages. This relationship of interdigitation of laminae is thought to allow for the partial suspension of P3 within the hoof capsule and the transference of tensile forces radially from P3 (Thomason et al; 2009) (figure 10).

In seeking to understand hoof function it is essential to grasp that the vast majority of weight is supported by the hoof walls through this lateral suspension from their inner border of the wall bears directly against the ground by the wall’s distal edge or bearing surface. The greater thickness of the wall toward the toe and the fact that the third phalanx is attached to the front half of the hoof wall indicate that more weight is to be supported there than by the thinner, less solidly anchored wall of the heels. Behind its midline, the hoof attaches via epidermal and dermal layers to flexible structures, such as the collateral cartilages, ill-suited to structural support. Further evidence of this dysfunctional dynamic of weight distribution is found in the declining density of primary lamellae in the wall as it approaches the heels (Bowker, et al; 2002). There are approximately 2.5 times more lamellae ridges per centimetre at the toe than at the heel. The greater density of lamellae at the toe indicates that this area provides greater support for weight. If the lamellae act primarily as slings holding the body weight in lateral suspension, they are subjected to constant tension, which increases with the speed of locomotion, except when the horse lifts a hoof or lies down. The consequences of excessive unnatural force distribution on the laminar connection are perhaps obvious.

In the normal foot, loading of the wall causes expansion of the hoof at the heels, and to a more limited extent at the quarter. Heel expansion is facilitated by the fact that heel horn is younger (and therefore moister) and thinner than the horn in other areas of the wall and so it is more elastic. This expansion presumably aids in diminution of the concussive forces associated with impact. Significant expansion therefore occurs only in those parts of the hoof wall which are not tightly bound to P3. There is evidence that the tensile strength of the laminae may actually lead to flattening of the hoof wall in the front part of the foot during weight bearing (Thomason et al; 2009). Shoeing has been shown to limit hoof expansion to some extent, apart from at the heels where the degree of expansion is unaffected, although the rate of expansion may increase.

How do we reconcile the fact that the epidermal hoof wall grows slowly towards the ground, retaining its tight weight-bearing bond with the underlying dermis, and yet the dermis remains in its original position adjacent to the coffin bone? Almost all cells are connected to their neighbours by a variable number of cell-to-cell junctions. These perform a variety of functions, such as allowing cells to communicate with each other, or forming an impenetrable barrier between the cells. There is a specialized type of junction called a desmosome which anchors cells to their neighbours, acting like a sort of intercellular rivet. The cells of the primary and secondary epidermal laminae are connected by desmosomes. It is thought that these desmosomes break and reform in a staggered sequence, allowing movement of the primary epidermal laminae over the secondary epidermal laminae, yet still retaining the strength of the laminar junction. This mechanism will be discussed in detail along with the functional anatomy of the remainig hoof structures in part 2 of this blog to published shortly.

Thank you for reading our article on Gross Anatomy and Physiology of the Equine Hoof.